Much of the U.S. has had a heck of a January. Freezing cold. Pummeling snow and ice. Frozen cars. Horrific world news. Who wouldn’t want a bit of February (and furry) fun?

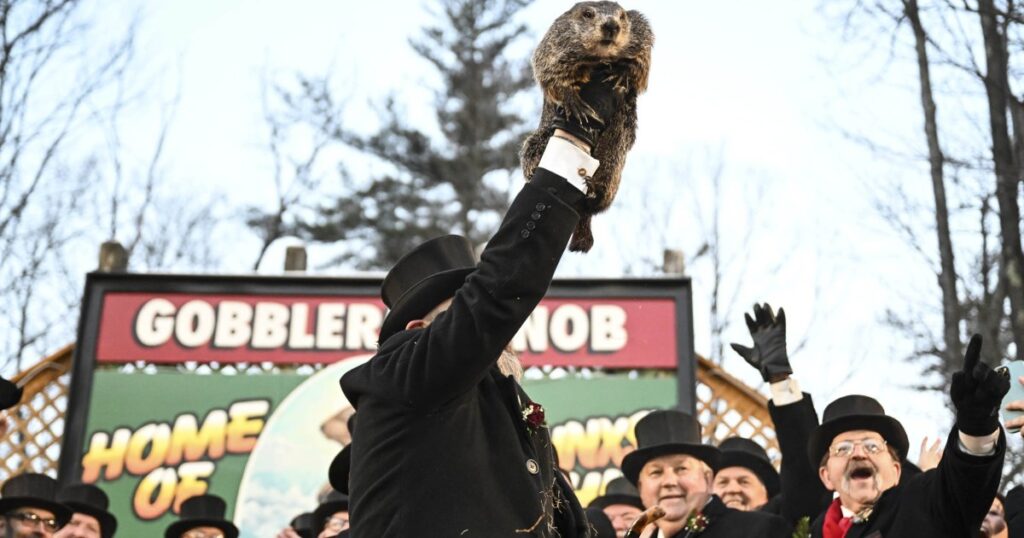

I’m a biologist who studies marmot behavior, so I may be biased. But my preferred midwinter festival is Groundhog Day. Today is the only holiday I’m aware of that celebrates animal behavior. And I don’t mean the behavior of the Homo sapiens who crowd into Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, to watch Punxsutawney Phil be pulled from his burrow to prognosticate about the weather by a bunch of cold, overdressed gentlemen. I’m talking about seasonal patterns of behavior, which biologists refer to as phenology.

Today is the only holiday I’m aware of that celebrates animal behavior. And I don’t mean the behavior of the Homo sapiens who crowd into Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania.

These patterns are fascinating for a lot of reasons, but they also can provide insights about the climate and environment relevant to humans. If only most humans listened to these signals as much as groundhogs do.

After 40 years and eight species, I could spend hours (and thousands of words) opining on why this animal deserves our attention — and not just one day out of the year. Groundhogs (also known as woodchucks) are one of the 15 species of cat-sized and charismatic (at least to me!) rodents called marmots. These days I spend much of my time keeping alive the world’s second-longest-running studies of a wild mammal — the 62-plus-year study of yellow-bellied marmots who reside in and around the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory near Crested Butte, Colorado. Groundhogs, like all marmots, spend their summers getting fat. Remarkably, studies have shown that they don’t have any physiological consequences of obesity. Marmots then spend their winters avoiding winter by hibernating, an extraordinary adaptation that permits animals to massively slow their metabolism and live off their fat the entire winter. Think about…

Read the full article here