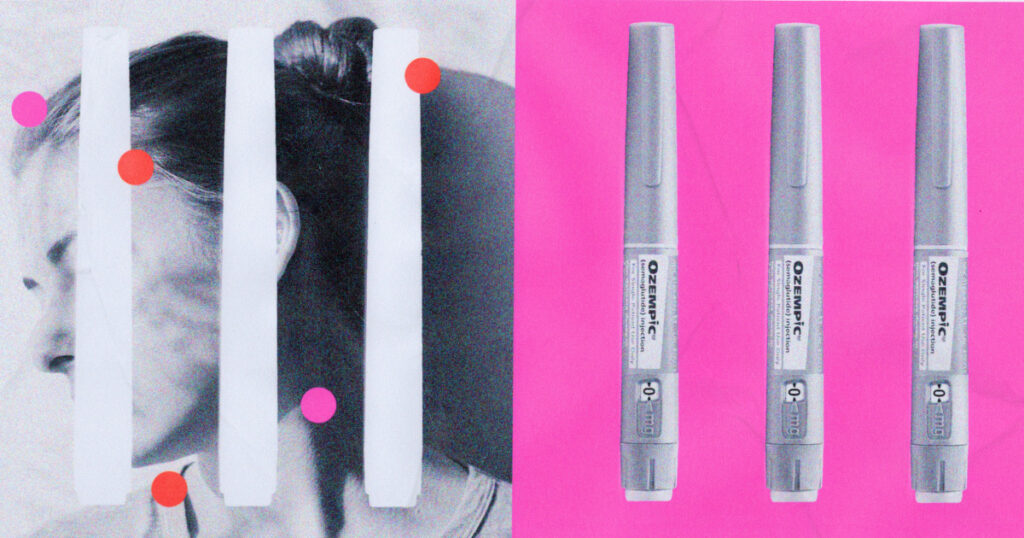

I haven’t been able to read anything about the diabetes drug Ozempic, and its increasing use (and abuse) for weight loss. I couldn’t bear to read that buzzy New York Magazine cover story — or the one that followed in The New Yorker. I had to mute the word “ozempic” from Twitter. I couldn’t even bring myself to read the heartfelt personal essays or tweets from other fat women that I respect and follow.

There was a moment there, a few years ago, when it seemed our thin-obsessed culture was shifting, ever so slightly.

There was a moment there, a few years ago, when it seemed our thin-obsessed culture was shifting, ever so slightly. We saw plus-size model Tess Holliday on the cover of Cosmopolitan UK and mainstream companies like Old Navy promising more size inclusivity. Conversations about body shaming and the dangers of constant dieting were starting to happen with more frequency in the mainstream.

But, I think we can agree, that moment has passed. Ozempic is not so much a cause as it is a very clear bellwether of this regressive shift.

I was a teenager when the “heroin chic” era of the 90s peaked, with its Calvin Klein ads and low rise jeans and Kate Moss quipping that “nothing tastes as good as skinny feels.” The highest fashion of my youth was designed to highlight just how thin you could (or really, should) be.

So it’s perhaps not a surprise that I also had an eating disorder in my 20s. For me, over-the-counter diet pills and appetite suppressants were a big part of my illness. An even bigger part? Keeping it all a secret. I never told anyone I was taking diet pills. I hid them from my friends and roommates, sometimes even buying them from pharmacies several towns over.

And yet, I didn’t always identify as someone who had an eating disorder. I was never officially diagnosed, because I never asked a doctor if what I was doing was safe. If I showed weight loss at an appointment, I was celebrated not questioned. As Dr. Deb Burgard said…

Read the full article here