These days, the threat of a government shutdown is as commonplace as lawmakers skipping town for recess.

This congressional term alone, the US has faced fears of a government shutdown no fewer than four times as lawmakers have failed to agree on long-term funding bills and passed last-minute, short-term patches instead.

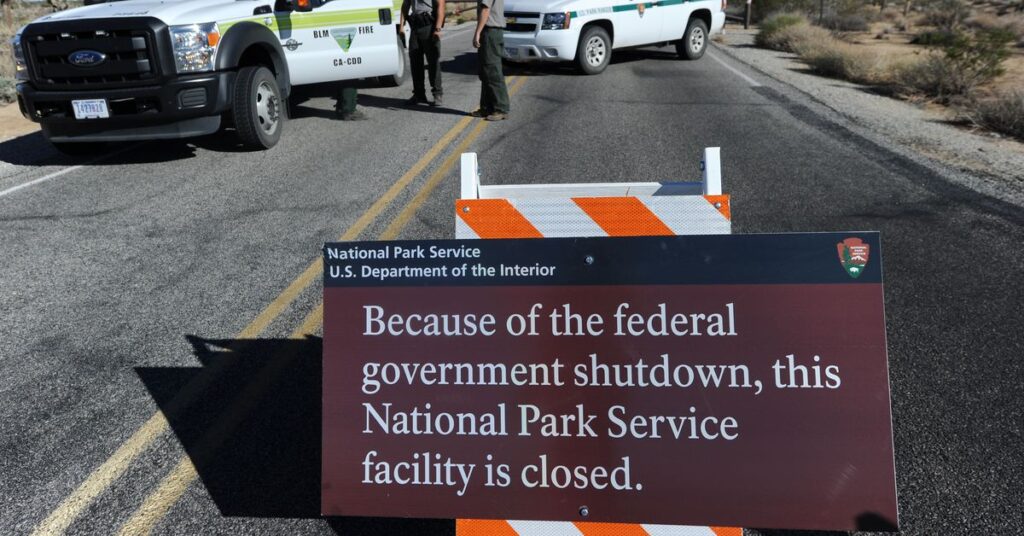

In 2019, the US saw its longest shutdown yet when former President Donald Trump tried to wield it as a political weapon in order to procure funding for his southern border wall. And overall, shutdowns took place more frequently in the 2010s than the prior decade.

For context, Congress must pass 12 funding bills each year that provide money for everything from the Department of Defense to the Food and Drug Administration. If they fail to do so by an end-of-September deadline, either they approve a short-term bill that buys them more time and keeps agencies funded or the government shuts down.

It’s now been almost six full months since the start of the fiscal year in October, and Congress has yet to approve multiple full-year appropriations bills. On Tuesday, lawmakers announced a deal to keep the government open and finally pass several of the remaining longer-term measures, potentially quelling shutdown fears for now.

Every time there’s another funding deadline, however, concerns about a potential shutdown ramp up. That’s because funding bills, like all legislation, are subject to growing polarization in Congress — and a faction of Republicans, in particular, benefits politically from threatening to shut down the government.

The causes of shutdowns have changed

Shutdowns aren’t totally new.

Modern-day shutdowns began in the 1980s after Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti issued an opinion stating that government agencies couldn’t keep operating if Congress hadn’t explicitly approved the funds they needed to do so. A handful of shutdowns happened in the 1970s as well, but they didn’t really close the government in the same…

Read the full article here